This underestimated film by Sean Connery would not have arrived without James Bond

Sean Connery came out of the relative darkness to win the James Bond game against Cary Grant and David Niven. The producers were certainly rewarded for their faith in the Scottish, which made the role of his success in five successful 007 adventures (only to return to “Diamonds Are Forever” and “Never Say Never Again”.) These films made him a familiar name, a sexual symbol and an international icon, but they undoubtedly overshadowed the rest of his career. But he had significant capacities beyond the research of a tuxedo, and two of his most substantial roles came to work with Sidney Lumet in “The Hill” and “The Offense”. Ironically, the first of these films may not have taken place without the passage of Connery on the secret services of His Majesty.

Although Connery has already started to get bored to play after “Dr. No” and “Goldfinger”, he had used his credit from these films to branch into more serious dramatic roles, appearing in “Marnie” by Alfred Hitchcock and “Woman of Straw” by Basil Dearden. Better still, “The Hill” by Lumet, which Connery admitted could not exist without his power of drawing at the box office after playing the Secret Agent Suave. He said to Playboy magazine:

“”[The success of Bond] had everything to do with that, of course. In fact, it might not have been done at all with the exception of Bond. It is a wonderful film with a lot of good actors, but it is the kind of film that could have been considered a non -commercial art property without my name. This gave producers financial freedom, trigger to do so. Thanks to Bond, I now find myself in a slice with only a few other actors and actresses who, if they put their names to a contract, means that finances will intervene. “”

Connery’s two films with Lumet may be underestimated because they are both rather dark and impactful images. I would say that Connery’s best performance occurred in “The Offense” in 1973, where he played a burned copper in the case of an alleged sex offender (Ian Bannen in a nominated BAFTA role) which could host his own deviant fantasies. Eight years earlier, he was almost as good in “The Hill”, playing a sardonic military prisoner who ran up against the authorities after the useless death of another detainee. Let’s take a closer look.

What’s going on in the hill?

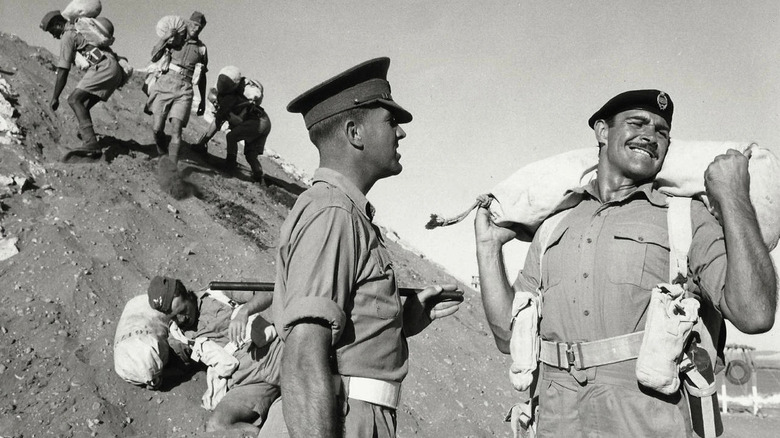

“The Hill” is a powerful drama during the Second World War in a British military prison in the Libya bakery desert. The installation is led by the sergeant with a hard nose, Major Wilson (Harry Andrews), a experienced man who prides himself on his ability to break the reprobates and transform them into dignified soldiers. His two immediate subordinates are the official sergeant of the staff Williams (Ian Hendry) and the kind sergeant of the Harris staff (Ian Bannen), two men who differ considerably from their approach to treat prisoners. It becomes very visible when they receive a new set of prisoners: the sweet deserter George Stevens (Alfred Lynch), the lazy black marketer Monty Bartlett (Roy Kinnear), the hardened drinker Jock McGrath (Jack Watson), and King Jacko Private Jacko West Indian (Ossie Davis). Among them, The Nut Wilson really wants to crack, Joe Roberts (Connery), a former squadron chief who is sentenced to having beaten his commander after refusing the order to embark on a suicide mission.

Once new arrivals are declared in shape by the prison doctor (Michael Redgrave), they are given to Williams for a severe introduction to life in camp. The privileged discipline method is the prisoners who rapid moarchants above the title hill, an artificially steep mound of bulk sand. Williams feels Stevens’ weakness and the target for additional punishment, making him die of extreme physical and mental exhaustion. Death brings the prison on the brink of the riot and causes a friction between the head screws while Roberts advances courageously to accuse Williams of murder. But who else will have the courage to support him and who will listen?

“The Hill” was written by Ray Rigby, a British screenwriter who had served in North Africa during the war and spent two spells in military prison himself. He channeled his experiences in the script, which launches a ruthless authenticity. Sidney Lumet’s documentary style approach also adds to realism, turning on the spot in an old fort in the south of Spain and often using a portable camera to provide a sense of movement and immediacy. The lucid cinematography of Oswald Morris really captures the flamboyant heat on the hill; I can’t think of another black and white film that looks so hot. The perspiration on the actors was however real, because the temperatures during the shooting climbed to 46 degrees Celsius (i.e. 114.8 degrees fahrenheit, for reference).

Sean Connery plays part of an excellent set in the hill

Despite prices later in life (especially his only Oscar for his performance in “The Untouchables”), the general consensus seems to be that Sean Connery was a better superstar than his actor. His performance in “The Hill” proves that he was very serious about the latter; Not only is the role of the anti-authoritarian Roberts not only, but it also shows how a humble team player could be. Although the film was built on the back of the enormous success of his adventures of James Bond and that he received the best billing, it plays a lot in a whole, offering an intelligent and vigilant performance which works in perfect synchronization with the distribution of actors of superb characters.

Indeed, Connery seems happy to support roles from afar in roles from afar, such as Ian Hendry as a malicious sergeant and cowardly Williams and Harry Andrews as a sergeant-major Wilson, who received a BAFTA appointment for his dominating performance. Overall, these two characters provide a fascinating criticism of authority in the circumstances of the kitchen pressure. Williams is an ambitious work, the importance of which is exaggerated at dangerous levels by the responsibility given to it, while Wilson is blinded by his devotion to the king and the country before Stevens’ death press it in the limitation of oppressive damage. The rest of the distribution all has exceptional moments too, in particular Ossie Davis and Michael Redgrave, before Connery has the chance to make a little size towards the end.

Confined almost entirely in the walls of the fortress, “The Hill” is a captivating and relentless film. More a prison drama than an out and out war film, it may have the most common with “12 Angry Men” by Sidney Lumet, who also focused on a courageous dissident for a mission for justice among a huge entirely male distributor. I also remember the “King Rat” by Brian Forbes underestimated (also published in 1965) and its exploration of the dynamics of power and social structures within a prisoner camp of war. Finally, the implacable barking authority and the moments of black humor recall the segment of the training camp for “Full Metal Jacket”, without the battle sequence in the second half to alleviate the pressure. It is not always an easy watch, but “The Hill” is comfortably stuck alongside the three as a classic nailed with Connery in the middle, just learned a chance to act. For this, we must thank James Bond.