Brazil’s climate credentials tested by search for oil off Amazon coast

At the river dock in Oiapoque, a border town near Brazil’s northern coast, Cleidiney Ribeiro launches her river boat.

“Progress is coming to Oiapoque,” he says optimistically, as he drives an hour and a half to where the river meets the Atlantic Ocean.

The Brazilian state-owned oil company Petrobras has just started exploratory drilling 170 kilometers from the Amazon coast, as Brazil opens the largest world climate conference, COP30, in Belém.

As host, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva told world leaders on Friday: “The Earth can no longer support the development model based on the intensive use of fossil fuels.”

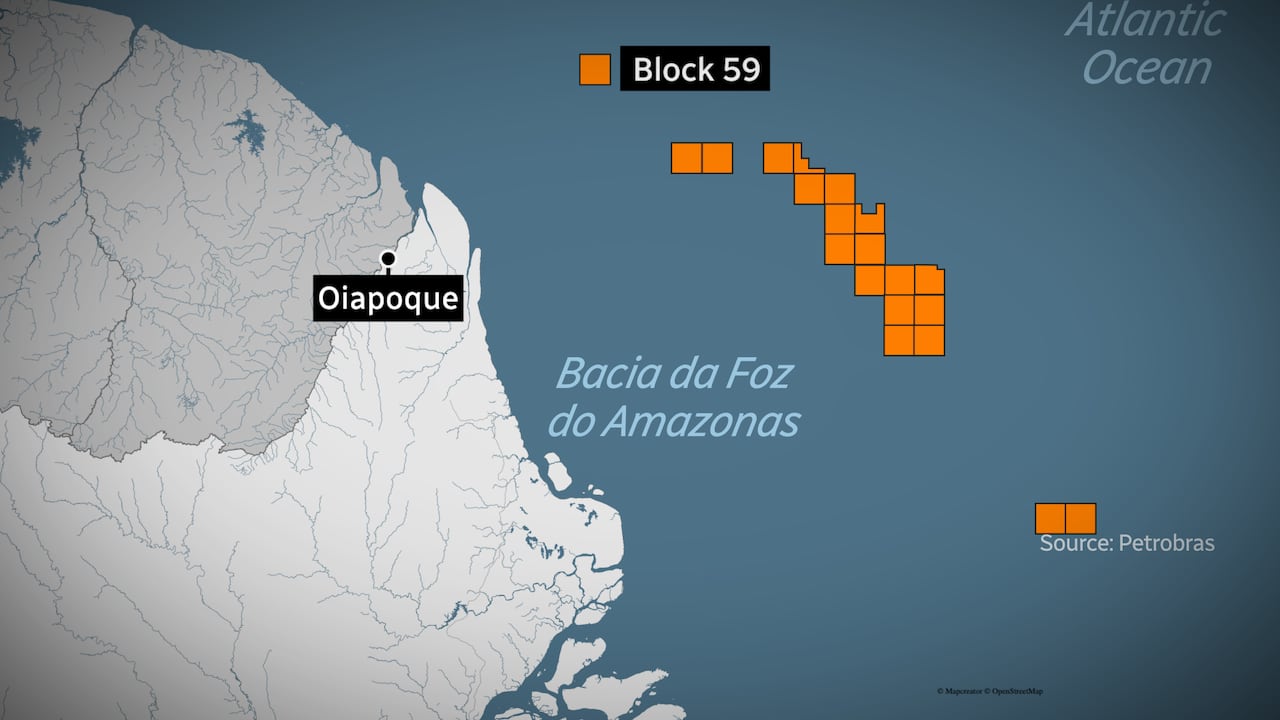

But his government is on the cusp of a new oil boom, if deposits are confirmed in the Foz do Amazonas basin, located 500 kilometers from the mouth of the Amazon River.

“It’s very problematic,” said Suely Araújo, public policy coordinator at the Brazilian Climate Observatory.

Brazil is already a major oil producer — the eighth largest — and Araújo said that “the government’s decision to increase this production in the midst of a climate crisis… makes no sense.”

Lula calls for energy transition at COP30

Since Monday, Belém has welcomed tens of thousands of delegates and observers to the Amazonian city of 1.3 million inhabitants. Accommodation is scarce — two cruise ships anchored offshore will welcome some of the delegates and the president is staying aboard a luxury boat.

COP30 will attempt to build new momentum to tackle fossil fuel emissions that contribute to global warming and urge countries to move more quickly towards sustainable energy sources.

“Brazil is not afraid to discuss the energy transition,” President Lula said at the leaders’ summit, promising to use part of its oil revenues to finance it.

But more than 1,000 kilometers to the north, in Oiapoque, the dynamic is entirely focused on oil; black gold, which could transform one of the most disadvantaged regions of Brazil, according to the government.

Hopes suspended on oil fields

“We all hope the oil is there,” said Romeu Costa, who manages the small Oiapoque airport, which serves mainly medical flights and the oil industry, with no commercial air traffic yet.

“This will develop the city,” Costa said, adding that real estate speculation is already growing in the city of 27,000 residents.

Twice a day now, a few dozen workers fly in from towns further south, then are transferred to helicopters to the drillship.

Petrobras holds the rights to Block 59, so far the only offshore territory with an exploration license to drill and confirm the size of deep oil deposits. But in an auction last June, the government awarded 19 additional oil blocks in the Foz do Amazonas basin to companies including Exxon Mobil, Chevron and a Chinese consortium. Companies must then apply for an exploratory permit.

Petrobras spent more than a decade working on an exploration plan and environmental testing, including building a large new wildlife hospital in Oiapoque to gain approvals. His efforts were rewarded just two weeks before the COP30 climate negotiations.

“This is the moment of our crowning moment, of our victory, of our work and our responsibility towards the country and the environment,” said Wagner Fernandes, who represents an oil workers union and works for Petrobras.

“A winning ticket”: Minister of Energy

Brazil’s equatorial margin deposits could be vast, with up to 30 billion barrels of recoverable oil, according to the ANP, the National Agency for Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels.

Brazil’s energy minister called it a “winning ticket” that could generate tens of thousands of jobs and fight poverty in the region.

But future drilling, if allowed, could encroach closer to the mouth of the Amazon River.

Protests last summer failed to stop the latest oil auction.

“I am very worried,” said Suely Araújo, who previously worked for state environmental regulator IBAMA, and refused to issue an exploration permit to Total Energies in a nearby block in 2019.

Brazil’s state-owned oil company Petrobras has begun exploratory oil drilling off the coast of the Amazon rainforest, raising questions about the country’s climate performance. Susan Ormiston, CBC international climate correspondent, visited on the eve of the COP30 climate conference in the region to see where climate policies and oil exploitation off the Amazon coast compete.

“It’s a fragile region and they will have problems because even if there are no accidents, oil production still generates a kind of permanent pollution, a silent pollution.”

Indigenous communities mobilize to oppose

A 20-minute drive from Oiapoque, through the Amazon rainforest, indigenous tribes live along the Curupi River in contiguous territories officially recognized by Brazil in 2002.

Chief Wagner Karipuna claims they were not consulted regarding their opinion on the oil license, which he says could endanger the waterways and lands they control.

“If this were to cause a leak, water has no boundaries. (…) It will contaminate our river, our fish, the game, the birds, everything will suffer,” he said.

At a rally last week, more than 50 indigenous leaders from the Oiapoque region signed a letter opposing the project, demanding a formal meeting with top Petrobras representatives.

Karipuna says he is skeptical about the promise of a job.

“You have to have higher education… to work for Petrobras, and we, the indigenous people, don’t have it. The government is deceiving us with false promises,” Karipuna said.

Indigenous groups are preparing for a major protest at the COP30 site in Belém to attract international attention and pressure on Brazil.

“I understand that it is difficult not to see [Brazil’s position] as inconsistent. We like simple things, yes or no, good or bad,” said Heloisa Borges of Rio de Janeiro, director of oil, gas and biofuel studies at energy research company EPE.

“We will still need a significant amount of oil and gas by 2050,” she said, citing International Energy Agency estimates that in 20 years the world will need between 24 and 55 barrels of oil per day.

“Just because we think we don’t want it doesn’t mean we won’t need it,” Borges said, adding that Petrobras has a “social license” in Brazil.

“Brazil is very proud of its oil and gas industry. Petrobras is a company that is in the popular imagination of almost every Brazilian.”

In Oiapoque, there is enthusiasm, but not everywhere, says Estafany Furtado, who works for Iepé, an organization that helps indigenous groups in the north.

“Those who are against [the drilling] are currently suffering from threats from the political class and supporters. I myself have suffered some threats,” she said.

Two years ago, at COP28 in Dubai, nearly 200 countries agreed to “move away” from fossil fuels. Since then, several countries, including Brazil and Canada, have reached record oil production.

President Lula describes the Belém gathering as the “COP of truth”. Its critics say the truth is that the world continues to expand on fossil fuels and global warming emissions continue to rise globally, but not as fast as before. It is an immense challenge for President Lula and the 50,000 international visitors expected in Belém.