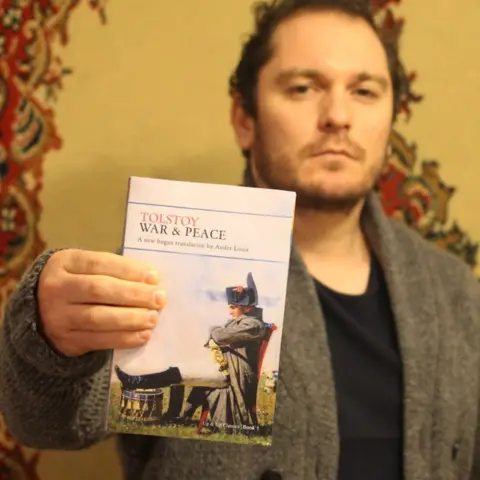

Australian ‘bogan’ gives War & Peace an irreverent remake

Other Louis

Other Louis“At that time, Prince Andrei went to Anna. He was the husband of the pregnant Sheila. As his wife, he was quite handsome himself.”

These lines are taken directly from a new translation of Leo Tolstoy’s epic novel War and Peace, set in the world of Russian high society in the early 19th century.

Except that it’s a “bogan” version translated by Ander Louis, the pseudonym of a Melbourne computer scientist who moonlights as a writer.

He poured a metaphorical can of Australian beer over the novel by converting Tolstoy’s prose into jargon that wouldn’t look out of place on the popular Australian sitcom Kath & Kim.

“That’s how they tell it in the pub,” Louis, whose real name is Andrew Tesoriero, told the BBC.

The 39-year-old started the project in 2018 as a joke, turning Russian princesses into “sheilas” and princes into “drongos”, but is now close to signing a book deal.

“The main reason I started doing it was to make myself laugh, and I figured if it made me laugh, maybe other people would too, so let’s put it out in the world.”

Bogan, a term that first appeared in Australia in the 1980s, initially referred to an “unsophisticated and uneducated person” with negative connotations, but not for Louis.

Getty Images

Getty Images“I never really thought of it as an insult, but more of a term of endearment,” he says.

And his version of the Russian literary masterpiece – which begins with the phrase “fucking hell” – is meant to be casual and irreverent.

“It’s just a good exclamation of surprise,” jokes Louis.

Elsewhere, a nobleman is a handsome dinkum, while the death of an important person is announced with “it’s a cactus.”

“It changes the tone quite significantly,” Louis laughs.

Accidental Tolstoy Expert

For years, Louis avoided reprising War and Peace, which was set during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s, due to his weight.

The novel is divided into 15 volumes as well as an epilogue, itself divided into two parts. With over 1,200 pages to go through, it is often considered the Everest of literature, with prose as insurmountable as the famous summit.

But in 2016, Louis joined an online community where participants commit to finishing the book in a year by reading at least one chapter – there are 361 – every day.

He liked it so much that he did it twice.

“I became a bit of an expert by accident,” he tells the BBC from Lilydale, a suburb of Melbourne.

Meanwhile, the part-time freelance author was writing a novel with dark psychological themes, so to lighten the mood, he began making War & Peace irreverent and funny.

And for more than six years, Louis’ project remained a little-known hobby that he pursued in his spare time, self-publishing the first two translated books of War and Peace and selling a handful of copies.

That all changed earlier this year when a New York-based tech writer stumbled across the bogan version, publishing excerpts from Louis’ book in which he describes Napoleon as a “nice guy”, the high-ranking Prince Vasily as “a pretty big deal” and Princess Bolkónskaya as “very hot”.

“Out of nowhere, it went crazy. Overnight, I sold 50 copies,” Louis says.

The father-of-two believes US interest in his bogan translation could be due to a “Bluey effect”, given that the popular Australian children’s cartoon has been the most-streamed show in the US for almost two years.

“Aussie-isms are all the rage there at the moment.”

How Bogan became its own language

At first glance, Tolstoy’s book, filled with the lives of rich and powerful Russians, seems worlds away from today’s Australia.

But Louis argues that bogan is the ultimate equalizer, because informal slang works across the social spectrum, whether in Australia or the world of Russian aristocrats.

“There are many different types of bogan,” Louis explains.

Mark Gwynn, a senior research fellow at the Australian National University who helps compile the Australian National Dictionary, agrees. “Bogans can be rich, poor or somewhere in between, so it’s more about how they behave, dress, socialize and speak,” he says.

He says that more recently the term has also been used affectionately to refer to someone considered a bogan or even in reference to oneself, such as the term “inner bogan”.

And speaking “bogan” refers to informal speech containing many local sayings, he says.

“Most Australians would know that if you said ‘speak bogan’ or ‘Australian bogan’ the language would be very informal with many slang and colloquial words and expressions, including some distinctly Australian words.”

But there is no direct translation of the term into proper English – it is uniquely Australian.

“Bogans can live in [both] rural and urban areas so that they are not equivalent to highlanders, boors, boors, rustics,” says Gwynn.

Bogans are also not the same as rednecks, as they can hold varied political views, while the British term “chav” – also generally used derogatorily to describe people from poor backgrounds – does not apply either.

These shifting bogan qualities along with Louis’ varied resume – cook, energy analyst, Uber driver, punk rocker, Tokyo resident – make him “oddly qualified” to create a bogan translation.

“When I draw on voices, it’s just from things that I’ve seen and done…across all these different backgrounds.”

Characters in his bogan version say “hello,” friends are “companions,” and those with questionable ethics are considered “shonky.”

The lovely ladies are “chick girls”, one of whom is so attractive she’s “hot as a tin roof in Alice” – a nod to the extreme heat of the Alice Springs desert landscape.

One prince is an “absolutely true legend” whose vibrant eyes “glow like bushfire” while another is a “bit of a yobbo” who thinks the others “carry on like a pack of galahs”.

Although his version is riddled with profanity – which the BBC cannot publish – part of its appeal is that it makes the book more accessible.

“The best feedback I’ve found is from people saying how much easier it is to understand what’s going on,” he says.

Louis compares himself to Pierre, the main protagonist of War and Peace, who represents “everyone” as the illegitimate son of a wealthy aristocrat who inherits an immense fortune, catapulting him into Russian high society.

He says he feels like the “clumsy jester” in the “walled garden that is traditional publishing” and that he has committed a kind of “literary heist.”

“I leaned over the fence… and just pinched the crown jewel – their most revered book – and took it into the pub.”

And what would Tolstoy – who, although born a nobleman, later renounced his privileged upbringing and wealth – think of the bogan version?

“Actually, I think he would enjoy it,” Louis said.